I am a native speaker of what we in the United States like to call the English language. Some derivative of the English language is the principal tongue spoken in many other nations that are not England or a part of the UK even if at one time they were. There are plenty of different derivatives of the English language spoken right there in England.

English as a second language is spoken all over the world, even, increasingly, in the US and England. In fact, and this will come as no surprise to you any more than the other painfully obvious observations I’ve made so far, English is spoken in one form or another and to one degree or another almost everywhere on the planet and argueably others as well. At this very moment, English words and phrases coded into radio waves are bouncing, harmlessly we expect, off other planets all over this neck of the Milky Way.

The point is that three hundred years of British Imperialism and a mere sixty years of American military, technological, political, and social preeminence established English as the de facto universal language of international communication, and the last two decades proliferation of personal computers, internet connections and more recently mobile telephones, have established new avenues for that communication across enormous physical, social, and economic boundaries, governed, or in some cases ungoverned, by an emerging new ensemble of forces, guidelines, and expressions, both formal and otherwise.

In the past, international communication has been driven at the highest political and industrial levels, but these recent explosions in communications technology have dramatically altered this dynamic. Systems of virtually instantaneous interactive exchanges of global proportions contain rapidly increasing numbers of ordinary people without specialized qualifications who have access to information of unprecedented variety and detail. For those with access to the Internet, events that were unimaginable one or two generations ago to even the most powerful members of society have become elements of contemporary daily routine for schoolchildren. Where once the points of contact between nations and states were principally limited to narrow conduits for leaders of government and institutions to address few but globally significant issues, now international points of contact are a vast and exponentially increasing network of often transitory and insubstantial exchanges between individuals and between individuals and private businesses.

Amazon and Ebay are thriving international marketplaces. A leisurely Sunday morning perusal of headline news can include the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the BBC, Pravda, and Al Jazeera, updated hourly if not more frequently. Google will provide millions of sources of information about any given topic. Chatrooms are crammed with teenagers from all over the world pretending to be people older and more interesting than they really are. Pornography is, of course, everywhere.

The implications of this phenomenom’s power to influence human affairs are legion and profound and beyond the scope of this enterprise, whatever it is, still, I would like to address one substrate of the process, and that is the coding of the message. The global compatibility of media asks a global compatibility of the language of the message and the language of the message has been fixed. There are millions of websites in hundreds of languages which give access to a national audience, but if you want to open a channel to anyone in the world to buy your product or read your blog, it needs to be in English.

The Chinese may still have something to say about this, but I’m guessing the communications lane of their road to global prominence and influence will be paved with English syntax and semantics and by the time they arrive they’ll be stuck with it just like we are.

And of course the brave and hopeful visionaries who continue to support Esperanto as the only viable alternative of the 200 or so universal languages that have been introduced over the centuries have been simply run over by the bullet train of virtual English ubiquity.

But the forces that brought this situation about were entirely unrelated to the suitability of the mechanics of the language for this purpose. There are problems with the use of English that arise out of the manifold sources and influences that have shaped its present form and perpetuate themselves through the sheer inertia of their use. A certain richness that results from this heritage comes at the expense of the consistent and comprehensive order that is characteristic of the individual languages out of which it evolved, particularly with regard to spelling and pronunciation. Here are some examples:

Bough, cough, tough, though, through, thought.

These are six different pronunciations of the same four letter, English language combination ‘ough’, none of which really needs more than two letters to represent it. What are those gh’s doing in there?

How about words that sound the same but are spelled differently?

Hear, here. Feet, feat. Ate, eight. You, ewe.

These contain letter combinations that sound the same but are spelled differently:

Do, two, shoe, grew, doom, flue, duty, brute, through.

Silent letters? Why?

Know, gnat, could, island, wrap, debt, often.

How about ie and ei? Which is it going to be? The rule is a joke, you just have to remember each word that contains them. This kind of thing goes on and on.

Why do we put up with it? I assume some of these difficulties might iron themselves out after a few centuries of organic evolution by default or accident, but I’m not convinced we have to wait, or should. It may be time for us to apply some organized, systematic intent to hotwire the process.

What follows is my attempt to construct a phonetic alphabet according to an organizational theme of my own design. Naturally any serious and competent scholarship regarding an undertaking of this magnitude warrants meticulous and exhaustive research into the language, word, and character etymologies of the various tongues that comprise the linguistic roots of English, the history and dynamics of their integration and evolution into the modern form we know, and the physiology of the human vocal structures as well as the attendant analysis of the actual sonic wave forms produced by them during the process of speaking.

Fortunately I am free of any actual investment in scholarship or competence, and was content to confine my research efforts to a cursory examination of the pronunciation guide inside the front cover of my 1963 American Family Reference Dictionary. In the face of my earnest conviction that a little knowledge is a dangerous thing, I proceed:

What is needed are uniform and consistent rules of spelling and pronunciation for the purpose of phonetic reliability and to forge a clearer and more proportional relationship between the written word and the spoken word it represents.

Clearly the first step is to assign each character a single unalterable sound, or phoneme, and conversely, represent each phoneme with a single character. Each word should be spelled with only the letters necessary to represent its vocalization. In this manner every word becomes a phonetic manifestation of the spoken word and each may easily be determined from the other according to simple principles.

Let’s look at the letter C. Does it sound like a K or an S? Yes, that’s the problem. But K always sounds like K and S always sounds like S unless it sounds like Z. How about this . . . get rid of C altogether. Use S for S and Z for Z.

Q and X are dipthongs, two phoneme combinations that can be represented by other letters, unless they sound like K and Z which we already have, so we don’t need them either.

We can make G sound like G and never like J, and Y exclusively a consonant.

That gives us a beginning with respect to consonants, now we have to give each vowel a single pronounciation, which is easy. The problem is that English has more vowel sounds than it has vowels. That means we can either eliminate all but five vowel sounds from the entire language or make up some more symbols. I think I’ll stick with the second option even though I admit I managed to lose some subtle vowel variations along the way that might not be long for a universal form anyway. Two billion Asians may not embrace all 42 English phonemes the way we had to.

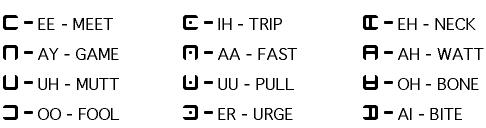

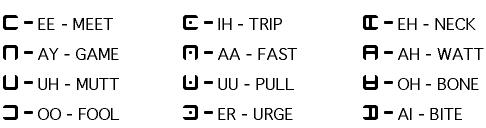

The problem for me is getting new characters to display on a website since I haven’t prepared a graphic, so for the time being I’m just going to underline suitable characters to change their pronunciation, although in actual practice I’d suggest putting a single dot over them instead. Let’s try this

| a - ah as in watt |

o - oh as in bone |

e - eh as in neck |

| a - aa as in fast |

o - uh as in mutt |

ei - ay as in play |

| i - ee as in feet |

u - oo as in rule |

ai - iy as in bite |

| i - ih as in trip |

u - uh as in pull |

|

The next hurdle is not with the representation of the letters but with the fact that many words aren’t pronounced the way they’re spelled in the first place. Take the letter “a” as used in phrasing: What a day. I need a drink. I bought a giraffe. It’s an “a” but we typically pronounce it like “uh” and if we want the written form to reflect the spoken form then the symbols will change based on the phonetic aspect rather than the spelling we are accustomed to and won’t be as easy to recognize visually until we are familiar with the new form.

Nonetheless, I submit these as fundamentally trivial changes that would make the language much easier to read and write and I believe English speakers could adapt relatively quickly and easily. Iven withaut eni praktis, it’s ferli izi tu undrstand, don’t yu think?

It’s my thinking that changes of this nature are virtually inevitable and I don’t see any point in waiting around for future generations to make them and wonder why we didn’t. And why haven’t we? Not for want of some real effort, there have been many attempts over the years to address the issue and those attempts continue. The International Phonetic Association has been around since the nineteenth century and has created a phonetic alphabet that represents about all the sounds a human mouth can make.

My objection is that they look goofy, but there are plenty of other players in the game as well, if you care to investigate.

The difficulty for me is that I tend to find these other characters or schemes unsatisfying. They’re either too awkward looking or use two letters to represent one sound. When I started thinking about this I wondered if it might not be a good idea to create an entirely new set of vowel symbols that would be similar to one another and distinguish them as a body from constants. This was in 1988 and I was heavily influenced by the fact that most electronic representations of letter characters were crude, rectangular arrangements of large pixels. Here’s what I came up with:

It’s obvious that the first failing here is that there is no lower case option, but many of these characters lend themselves to vertical adjustment for a similar effect, with variation of the open arms of the symbols above and below some baseline. I’ve also included some symbols for dipthongs long A and long I, and left some vowel phonemes out altogether. I know. Sue me. I like them anyway and think they look cooler than any of the options I’ve seen so far.

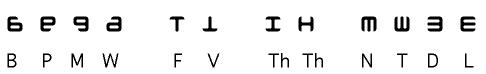

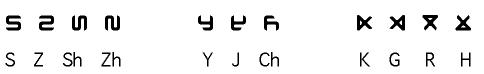

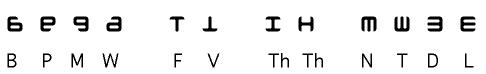

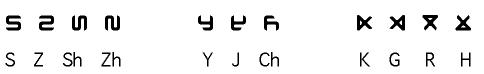

I also think something like this is everything that’s necessary for a solution to the problem, but once I got started I couldn’t stop, I was compelled to tinker with the constants as well. I decided to select groups of four consonant sounds that are shaped by the mouth in a similar fashion and represent the unique elements in each one with different orientations of a single symbol. For example, the first group are letters that are pronounced as buh, puh, muh, whu, all shaped by first pressing the lips together. The second group is fuh, vuh, beginning with the upper teeth against the lower lip. The third group uses the tip of the tongue against the upper teeth, the fourth group uses the tip of the tongue against the front of the palate and so forth.

There are plenty of problems with this character set as well, but I was doing this for fun and have no illusions it will lead anywhere so it doesn’t need to be airtight. I designed it because I thought it might be an interesting thing to do, so keep in mind I am not serious and have no interest in defending or championing it in any way. I just wanted to demonstrate one approach to the problem and put together something that appears 21st century. This is what it looks like in quotes from Saul Bellow and anon:

The word Alphabet is a conjunction of the names of the first two letters of the Greek Alphabet, Alpha and Beta. I thought to call my effort after the second and third letters, Beta and Gamma, or Betagam, but of course whatever it is called, it is still an alphabet, so this is just silly. But I didn't realize it until I had made a nice graphic for the title of this page and am too lazy to change it, so Betagam it is, at least for the time being, unless I decide I like Alphabet Noir better.